Wilderness: Chapter 5

The Grasscutter Rat: In which we flee our second war zone and find our path

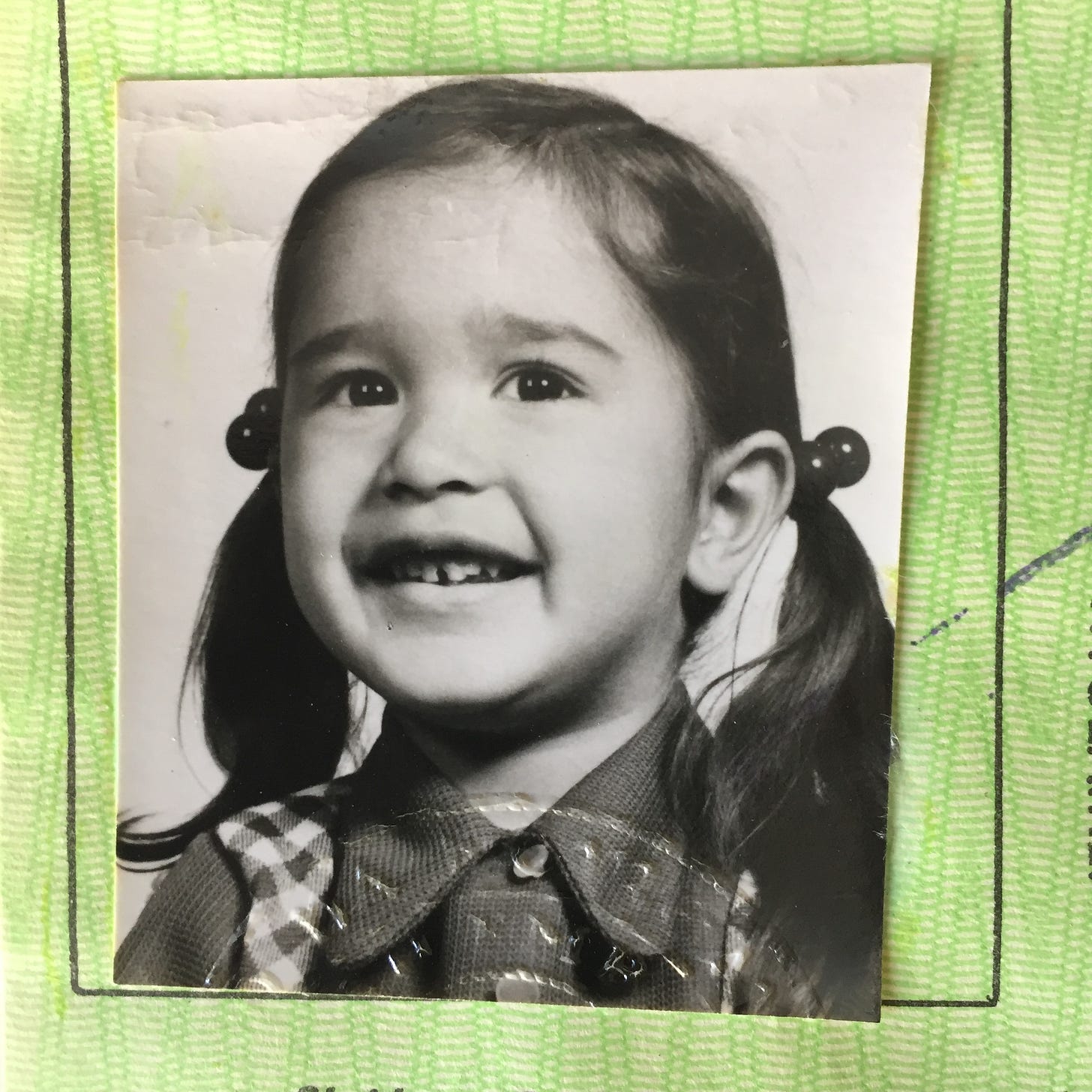

This is the sixth chapter in Wilderness: In Search of Belonging. My nature memoir traces my journey growing up as a dual heritage child in a white family in predominantly white, rural Britain—a place where I never quite fit in, and my sense of belonging always felt out of reach.

Now, as an adult, with my husband and daughter, I have moved to a remote part of Somerset to begin a mini conservation project. This is my story of our rewilding adventure, an exploration of how nature can help us heal, and a deepening understanding of what it means to truly belong.

I remember fragments from when I was five, and we were living in Nigeria: the time I stood in front of the long grass at the bottom of the garden, listening to the rustling of insects and knew I wanted to be a zoologist but wasn’t brave enough to venture any closer; lying in bed at night looking up at the mosquito net, which sagged in the middle, and being terrified that a giant spider would creep across it, the net dipping ever closer to my face as I slept.

Once James, my new step-father’s cook caught a greater cane rat or grasscutter that was living in the drain under our house. Cane rats can grow up to 60cm and weigh between 3 to 5 kilos, one of the largest rodents in Africa, they’re considered a delicacy and are now being farmed in parts of Africa. The cook invited me to eat the rat with his family that night, but I was too shy.

Another time my mother had set up a paddling pool for me in the cool inner courtyard of my step-father’s house. I was in a white vest and pants; she was in a beautiful African print dress, ready to go out. She hosed me with cold water for a joke; outraged, I snatched the hose back and turned it on her. She was, of course, furious.

In 1975 there was a military coup. It was, fortunately, bloodless. Colonel Joseph Nanven Garba announced on Radio Nigeria that he and other army officers were removing General Yakubu Gowon as head of state and commander-in-chief. Gowan was out of the country at the time. My step-father, whom I’d called Uncle James since I first met him when I was two-year-old, had returned to Nigeria as a Professor and Head of Department of Government at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria. He’d been trying to bring resolve the protracted civil war in Nigeria peacefully for years, and perhaps, as a result, was thought to know too much about Nigerian politics by the new leaders.

We were told we had 24 hours to leave the country.

Whilst I was at nursery, my parents ran round the house with friends, pointing to the items they wanted to keep, and their friends promised to ship them to the UK when they could.

Years later we would receive a random selection of furniture: a black leather pouffe, a walnut rocking chair with roses intricately carved down the sides, a set of side tables resting on wooden elephants with real ivory tusks, a collection of Yoruba brass sculptures.

The day we were deported, one of my parent’s friends quickly made me some gifts for the journey; I boarded the plane that evening clutching a tie-dye bag filled with coconut macaroons, a patchwork dog called Henry, and my two favourite toys: Red Teddy and Yellow Teddy. I still have them today, Henry and the bears, safely tucked into my daughter’s bed.

The rest of our luggage was packed into our car, which was shipped overseas. When the car reached England, a few days later, it had been completely emptied of all our belongings and stripped back to the chassis: even the tyres and the hub caps had been stolen.

I was distraught. I’d left my only other toy - a green Corgi car with doors that opened and a purple interior - in a side-pocket. It had been taken too. The new government froze my fifty-year-old step-father’s bank account and seized his savings and pension.

So now we were in the UK. We had nothing: no house, no income, no work, and of course, no car.

We only had what were carrying when we boarded the plane.