How much of other people's lives can you steal to put in your books?

One Year Later and The Stolen Childhood

Hi there!

I’m Sanjida. For those of you new to , I’m an award-winning writer and I write about writing, wildlife and wilderness. Subscribers enjoy one or two posts a month from me, a back-stage pass to the writing life and mini doses of inspiration from the natural world. Members receive ALL my content, including exclusive resources on how to become a better writer, read my book, Wilderness, before anyone else (which is about rewilding and belonging), and receive a 10% discount off mentoring sessions with me.

If you’ve missed them, here are a couple of posts you might like:

Wilderness: In Search of Belonging

A Simple Way to Come Up with Compelling Ideas

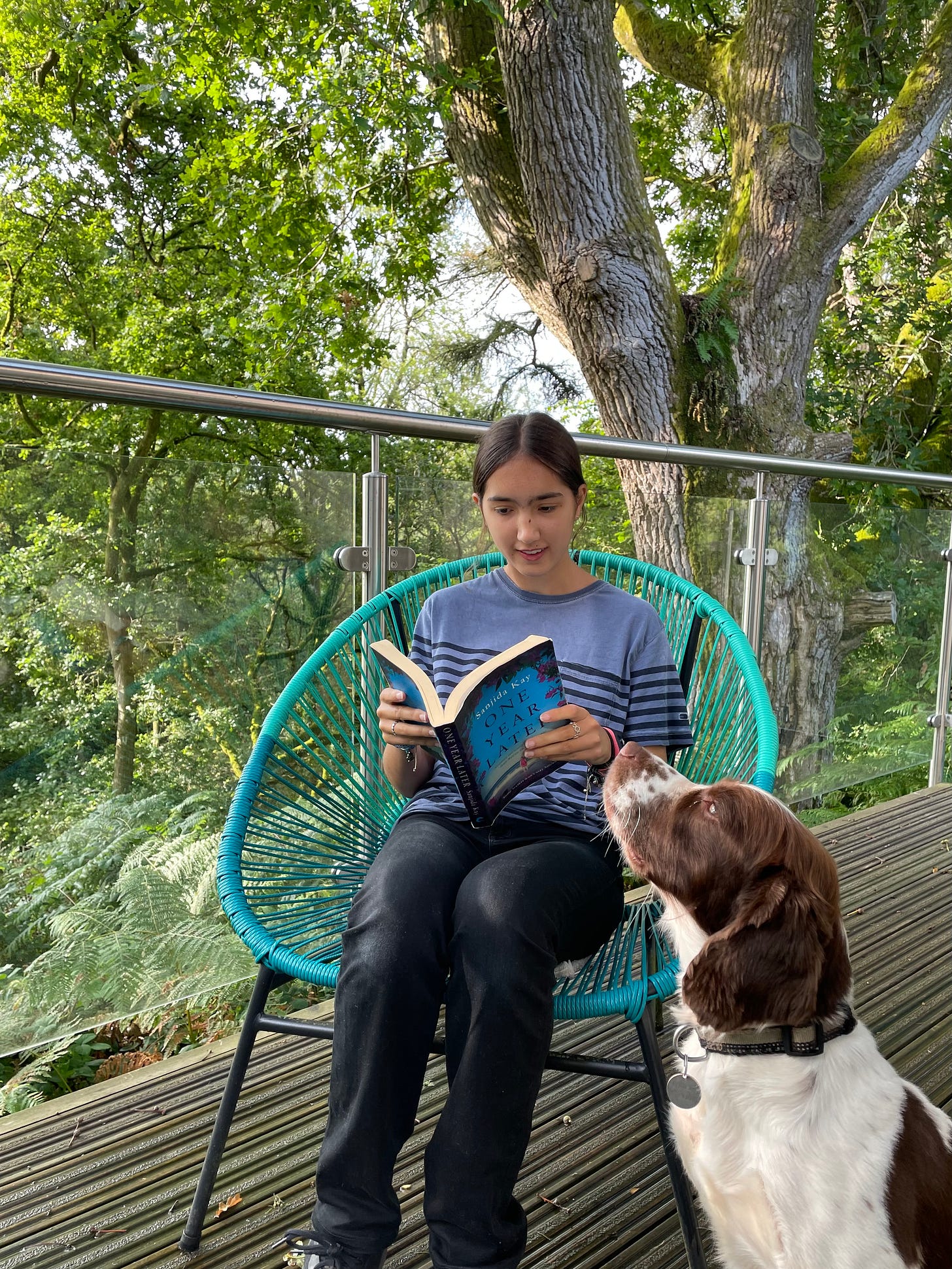

My daughter, Jasmine, and I recently came back from a couple of days staying in a treehouse. It wasn’t as precarious as it sounds (we took the dog with us!) as you walk in on level ground, but are then balanced on the edge of a disused quarry, nestled amongst giant oak trees.

It was stunning - a one-room apartment, one whole side of which was glass, a balcony that hung out into the oak canopy and an outdoor bath beneath the leaves and the acorns. We had planned to chill out and had brought lots of books.

As Jasmine unpacked, I realised she’d taken my books. Specifically my Sanjida Kay thrillers. She read the first one, Bone by Bone, a couple of years ago, which seems fair enough as the headteacher at her previous school had told the nine year olds they could read it.

At fourteen, she’s decided she’s old enough to read the rest. Sex scenes and all. Oh boy.

I tried not to watch her as she curled up on the burnt-orange sofa and read One Year Later.

This is what One Year Later is about:

Since Amy’s daughter, Ruby-May, died in a terrible accident, her family have been beset by grief. One year later the family decide to go on holiday to mend their wounds. An idyllic island in Italy seems the perfect place for them to heal and repair their relationships with one another.

But no sooner have they arrived, than they discover nothing on this remote island is quite as it seems. And with the anniversary of the little girl’s death looming, it becomes clear that at least one person in the family is hiding a shocking secret. As things start to go rapidly wrong, Amy begins to question whether everyone will make it home …

Suddenly, Jasmine’s brow furrowed and she looked puzzled. ‘Wait, didn’t I say this?’ she said slowly.

A little later: ‘What! And this! I said this too!’

Ruby-May, the little girl in One Year Later, is not my daughter nor even remotely like her. But I had borrowed some of the things my daughter said and did as a child that I thought were funny or poignant and gave them as memories to Amy Flowers, the mother in my story.

‘Remember when Ruby-May had chocolate cake for her birthday? She put the pointy bit in her mouth, and then she put both hands on the other end and she stuffed the whole piece into her mouth at once!’ says Theo.

‘You know that time when she heard Uncle Nick singing?’ says Lotte, ‘She put her hands over her ears and she kept shouting, “Stop, stop, you’re going to break that song, Uncle Nick!”’

Luca clears his throat. ‘Do you remember the time I say to her, “I love you,”? And she reply, very satisfied with herself, “Yes, you love me!”’

Tears are running down Luca’s cheeks. I glance at Matt and Amy to see if this is going to break them. Amy tries hard to smile.

She says, ‘Do you remember that time when I couldn’t find my best bra? And then Ruby-May came back from the park with Daddy and she was wearing it!’

‘Fastened at the front, with the boobs on her back!’ says Theo, ‘Daddy hadn’t noticed she was wearing a lacy pink bra. On the swings!’

‘I tried to take it off her and she got very annoyed. She said it was her -’

‘Rucksack!’ shouts Lotte. ‘And when you tried to put in on, in the bit for your boobs, you found a Peppa Pig plaster, a gummy bear and a toy stethoscope!’

One Year Later by Sanjida Kay

What can I say? This is what authors do. Some might say it’s stealing. I like to think of it as borrowing and repurposing.

‘You should have asked my permission,’ Jasmine said.

‘You were eight when I wrote it.’

‘It’s my copyright,’ she said.

Do writers have hearts of ice?

Graham Greene wrote , ‘There is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer.’

In his 1971 autobiography, A Sort of Life, Greene describes recovering in hospital from appendicitis. There was a boy of around ten on the ward who had broken his leg playing football and who died unexpectedly. When the child’s parents arrive, Greene, alone amongst all of the other patients, lies watching and listening. He wrote:

‘There was something which one day I might need: the woman speaking, uttering the banalities she must have remembered from some woman's magazine, a genuine grief that could communicate only in clichés.’

There is something breathtakingly brutal about Greene’s words, almost sociopathic, seeing the death of a child and the family’s grief as material for his writing.

And yet, is this not true of many authors?

Writers have an ability to be touched, absorbed, deeply moved by events they witness, but are also able to regard those same events clinically, dispassionately, even as inspiration for future scenes in their work.

There is a positive aspect to this: I believe a kind of magical alchemy is at work here, where a writer turns death and loss, laugher and pathos, into something beautiful, like turning a hard nugget of rock into a diamond through the pressure of their words and their feelings and the weight of their observation.

In spite of Greene’s words, most writers, whilst admitting they are very similar, would also describe themselves as empathic.

Is it empathy?

According to one academic definition, ‘Empathy is the ability to enter into the life of another person, to accurately perceive their current feelings and their meanings’1

When someone is being empathic, they borrow the other’s feelings in order to fully understand them, but they are always aware of their own separateness. They know, that no matter how acute the feelings of the other are, they are not their own. An empathic person senses the inner world of other people as if it is their own, without ever losing sight of that crucial ‘as if’ quality.

Sympathy, in contrast, is when the listener takes on another person’s feelings and circumstances as if they were in the other’s place.

Sympathy is less useful in life - and in fiction - because by being sympathetic, you are losing this essential difference, the as if-ness, and are imagining what you would feel in that situation as opposed to what the other person feels.

It’s perhaps clearer when we look at the German words, which are at the root of our own concepts of empathy and sympathy. Sympathy in German is mitgefühl - literally feeling with. In contrast, empathy is einfühlung - which is one feeling. Karla McLaren describes how this word first appeared in her book, The Art of Empathy.

In ‘the German philosopher Robert Vischer’s 1873 PhD dissertation on aesthetics, Vischer used the word to explore the human capacity to enter into a piece of art or literature and feel the emotions that the artist had worked to represent – or to imbue a piece of art (or any object) with relevant emotions.’2

Empathy is crucial for a writer. However, unlike say, a nurse, a writer will feel your pain and understand your situation, but then they might write about it later.

An obscene betrayal?

Whilst understanding all of this, I am still mindful of those writers who may have taken liberties with other people’s lives: Christopher Robin, for instance, believed for many years that his father, AA Milne, had stolen his childhood and turned it into a best-selling series of books about his beloved bear, Winnie the Pooh.

The novelist and journalist, Julie Myerson wrote about her son’s drug addiction in My Lost Son, which he described as an obscene betrayal:

'She's a writer and like a lot of writers she is wrapped up in her own world - even if the worlds they are creating aren't quite true, they become true to them anyway.' Jake Myerson

Right now, I’m writing a memoir, Wilderness, which I’m serialising here on

. There are even more thorny dilemmas when writing about your version of your life in a non-fiction book, which necessarily involves other people - something to discuss another day perhaps.But for now, and in my fiction, I know it’s a fine line to tread: I like to believe that what I’ve taken, I’ve repurposed, refashioned, turned into something other, hard and beautiful, a polished stone with a heart of truth.

Back from the treehouse, when my husband hears of our discussion, he says, ‘Perhaps you can share your royalties with Jasmine?’

I think about Boden jeans and Clarks school shoes, new notebooks from Paperchase, of books and bookcases; horse riding lessons and ice skating, ice cream at the beach and popcorn in the cinema, cake in cafés, cheese sandwiches at Paddington Station, train tickets and Cornish holidays.

‘Oh, I already have,’ I say, ‘I already have.’

What do you think? Is it acceptable to ‘take’ events from one’s real life and repurpose them in your work?

Where would you draw the line?

Kalisch, Beatrice J. “What Is Empathy?” The American Journal of Nursing, vol. 73, no. 9, 1973, pp. 1548–52. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3422614. Accessed 19 Sept. 2024.

The Art of Empathy by Karla McLaren, 2013

A tricky question, and one I often consider: I agree about the sliver of ice in a writer’s heart. We will take from our experience. Following my older sister’s death in 2009, my family was blown apart by a whirlwind of grief-fuelled emotion which has never really settled. I’ve ’used’ all of this in my novels, and I would understand if another sister of mine would never forgive me for a poem I wrote and published a few years later — but I wouldn’t know, because there’s not much communication between us.

The loss of my first baby, FORTY years ago (what, really?) has permeated everything I’ve written, and there’s usually a lost child — in some sense — in my books. I think that’s why I empathise so strongly with the mothers of the ‘lost’ asylum-seeking sons I’m involved with.

Thanks for a great and thoughtful piece of writing, Sanjida!